On Wittgenstein, Subahibi, Existenialism & Evangelion

Live happily

Analytic philosopher Ludwig Josef Wittgenstein (quoted above) once famously thrust a fireplace poker in the face of fellow philosopher and rationalist Karl Popper at a conference at the London School of Economics, daring him to give him an example of any absolute moral rule. This scene in history, alongside Poppers iconic reply of ‘Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers’, remains one of the more fascinatingly soapish philosopher mind-battles of the 20th century, with whatever was going on between Camus & Sartre coming in at a close second.

Violent hijinks aside, Wittgenstein is and remains one of the more interesting scions of philosophy still venerated by graduate students today. Though, admittedly, analytic philosophy is not my cup of tea, Wittgenstein walks a thin line between the analytic schools of thought and the more mystical, theory-adjacent philsophers that surfaced in 1960s France after his death; famous names like Giles Deleuze are arguably indebted to Wittgenstein’s initial interrogations into ontological sense and value.

Though the quoted precepts above, on the sense of the world lying outside the world, may initially come across as cold and negative diminutions of the value of humanity that stress the irrationality of human existence, Wittgenstein’s thought refuses the categorisation of pessimism.

Yes, perhaps what we know is limited by our own frame of references and, yes, perhaps we can never know anything beyond this world because such an escape is categorically unthinkable. Yet, does this not suggest at some fantastical relief somewhere just beyond the line dividing the world from what is not-the-world? Yet, does this not point, not merely to solipsism, but to the increased importance of human-to-human connections? If our sense of the world doesn’t come from outside of the world, than where else can we seek for it than in heads and hearts of our brothers in arms?

Say, for instance, you see someone you know experiencing a broken leg or a headache. Can we ever truly empathise with their sufferings? Though common sense says yes, obviously, some more stringent philosophers, the neo-Platonic deniers of material reality as a source of knowledge, would argue otherwise. Yet, even if we can’t exactly empathise with the other’s suffering, surely we can at least sympathise with it? From an idealist perspective, even this sympathy is not a true knowledge of the experience of the other; rather, when we feel the pain of others, we are merely imagining their feelings and thus according our sympathy/empathy to them. Life is just so many imaginations to the idealist philosopher - all our experiences of reality are mediated by our uniquely human ability to fictionalise and story-tell.

Yet is this, too, not a concept of unimaginable potentiality? If all we know is a story, why not tell it differently? Here, sympathy with the people around us figures as an gold-standard opportunity for imaginative exercise; by relating to our acquaintances we awaken ourselves to our full potential for fictionalising, thus priming ourselves to rewrite not only what they feel about us, but what we feel and what we consider ‘true’ about the world'.

Thus, by positing that the subject is the limit of their world’s value, Wittgenstein’s words allow for the possibility of love as a gooey lubricant - of love for the other as the only tool capable of stretching our cramped perspectives and rearranging our limits. By positing that value does not exist within the world but, rather, in the attitude with which we approach the world, Wittgenstein in fact gives to us the possibility of a dumb love for the world around us, independent of any external will and of our own limit-setting accord.

Last week I had the bizarre chance to be engaging with two very existential, and perhaps two very Wittgensteinian, pieces of media at around the same time - namely the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion and the ‘ergoe’ visual novel Subarashiki Hibi, or, in English, Wonderful Everyday.

Evangelion is potentially the most critically acclaimed anime of all time, though its anime-typical fan service and weird sexual mores makes it difficult for me to casually recommend to the unseasoned anime-watcher. Though my initial viewing of the show (and The End of Evangelion, the series’ alternate-ending-turned-movie) had solidified it as one of my favourites in the genre, the paucity of good television options had led me to rewatching it in its entirety at the beginning of June; I find, with favourite books/music/food, that time calls into question the quality of these past ‘perfect’ artistic experiences and forces one to always be rewatching/rereading/re-eating, in order to be sure of one’s own tastes (though, admittedly, this is more of a me-problem, as prone to self-doubt as I am).

Evangelion not only held up to my rewatch but surpassed everything it had made me feel 5ish years ago. Whilst its soft philosophical themes went largely over my head during my past watch, with younger-me needing to toil through various ‘Evangelion EXPLAINED’ Youtube videos for finality and coherence, I found that, now, the show’s themes and ideas resonated with me on a deeper and darker level - maybe its just that my 4 years of philosophy study has actually contributed to my increased critical awareness, maybe I’m just in a different emotional place than I was when I was 17 (thankfully). In any case, Eva’s final two episodes, though very (erroneously) disliked by fans upon their release due to their sloppy animation and lack of action battle scenes and what have you, awed me in how flawlessly they translated the Wittgensteian notions of expanding the self’s limits with the help of those around you, onto the medium of anime.

Specifically, through deconstructing the typical anime art-style back to its storyboarding phase, a choice critcised much by fans who blamed a lack of budget and 'laziness’ on the part of the shows director’s, the last two episodes of Eva take protagonist Shinji Ikari’s world apart by its very seams; here, Shinji is placed into a world of his own making where he is its solipsistic God, only to find that, voided of persons as it is, this narcissicist fantasy affords no meaning and no love. Coming to the opposite conclusion as the characters in Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, Shinji realises that hell is NOT other people - rather, it is other people through which all our self-meaning stems from.

Moreover, again echoing Wittgenstein, Shinji realises that his negative self-perceptions are, too, fungible - if the world’s limits are dictated by him, what is stopping him from loving himself, from transformation, from being whoever he wants to be?

Shinji: I've got it. This is also a world.

The possibility within me.

The me at the moment is not always the me as I am.

There are many of myself.

Yes. There must be a me who is not an Eva pilot.

Misato: Considering that, the real world itself is not always bad.

Shinji: The real world might not always be bad.

But, I hate myself.

Makoto: It's your mind that conceives that the reality is bad

and hateful.

Shigeru: The mind which confuses Reality with the Truth.

Maya: The angle of view, the position. If these are slightly

different, what is inside your mind will change a lot.

Ryouji: There are as many truths as there are people.

Kensuke: But there's only one truth that you have,

which is formed from your narrow view of the world,

It is revised information to protect yourself,

the twisted truth.

Touji: Oh, yes. the view of the world that one can

have is quite small.

Hikari: Yes, you measure things only by your own small

measure.

Asuka: One sees things with the truth, given by others.

Misato: Happy on a sunny day.

Rei: Gloomy on a rainy day.

Asuka: If you're taught that, you always think so.

Ritsuko: But, you can enjoy rainy days.

Fuyutsuki: Through different ways of conceiving, the truth

will change into very different things; it's a weak thing.

Ryouji: The truth within a person is such a cheap thing that

people wish to know deeper truths.

Gendou: It's only that you're not used to being liked by people.

Misato: So, you don't have to look to others' faces.

Shinji: But, don't you hate me?

Asuka: You idiot! It's only you who is always trying to believe

that.

Shinji: Yet, I hate myself.

Rei: Those who hate themselves cannot love or trust others.

Shinji: I am wicked, cowardly, weak and ..

Misato: If you know yourself, you can be kind to others.

Shinji: I hate myself.

But, I might be able to love myself.

I might be allowed to stay here.

Yes. I am nothing but I.

I am I. I wish to be I.

I want to stay here!

I can stay here!

People: Congratulations!

Shinji: Thank you!

Thank you, my father.

Good bye, my mother.

And to the all the children,

Congratulations!

A musical transition, of sorts

A Musical Transition, of sorts

There are not enough words in the English language for me to describe the impact Subarashiki Hibi had on me; the plot too, is layers too complex and bizarre for me to put into words. So, echoing Wittgenstein’s adage that one should pass over in silence what one can not say, I will forego a lengthy description of the indescribable levels of alternating visceral disgust and existential catharsis that I experienced throughout my read of this 40-hour-long trek of a visual novel. Instead, I will focus on its intersections with both Wittgenstein’s logical limits and the oeuvre of Evangelion.

Whilst Subahibi directly quotes Wittgenstein various times across its numerous chapters and routes, its connections to Evangelion are also striking, and extend pass their pre-cursively-demonstrated soundtrack similarity (as evidenced above, they both make critical use of the same Bach track). Simply put, the characters of Subahibi, though put through much, much worse situations of torture and suffering than any member of the Evangelion extended universe, experience the same alienation and lack of faith as Shinji does. Like Shinji, and by extension like Wittgenstein himself, the characters of Subahibi strive towards some tangible truth/God to explain their purposes to them and to justify the extent of their torments; within its layered, fugue-like narrative where the boundaries between dream, reality and schizophrenic hallucination are eternally-permeable, it is no wonder that Subahibi’s cast fights to find something true and real to depend on.

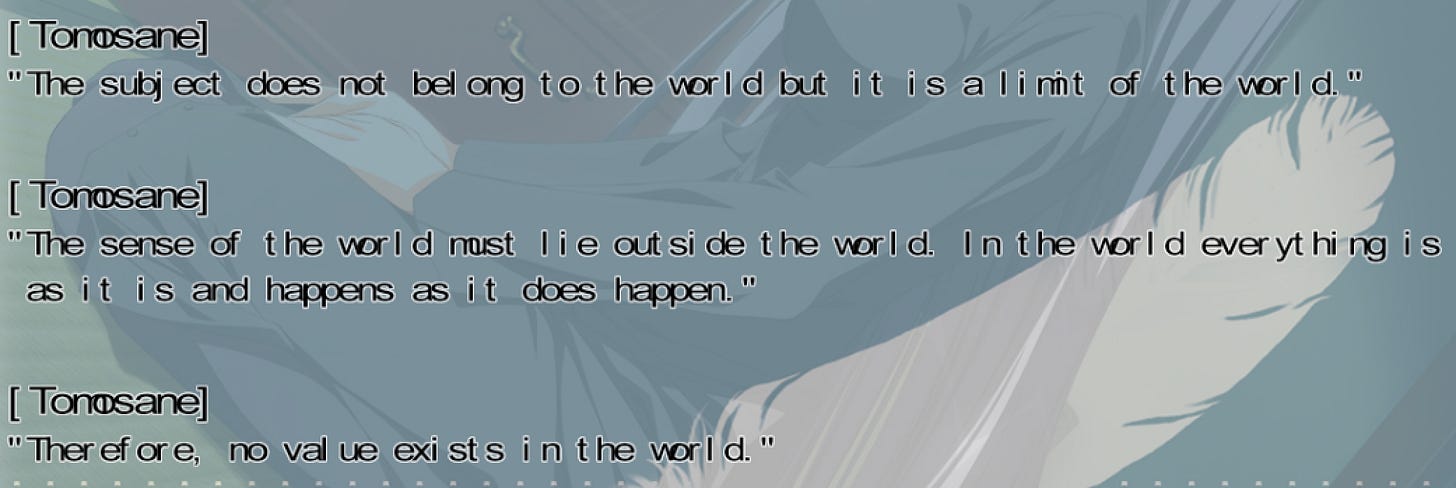

It is no wonder, then, that the words of Wittgenstein provide so much solace for the characters of Subahibi, ensconced within their own brains as each of them are and perpetually at the risk of having their perspective erased with the coming of a next chapter and a new protagonist.

— Ludwig Josef Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Yet, also like Shinji, Subahibi’s characters recognise the importance of the interpersonal; reflecting on the how the limit of one’s world depends on oneself, the VN’s characters use their connections with others to stretch this limit.

Some screenshots:

It is difficult to end this essay conclusively, with any coherent statement on how one should take the combined philosophical underpinnings of Evangelion/Subahibi/Wittgenstein’s philosophising. All I can say is that, for me, the conjunction of these three works has moved me unspeakably and I won’t be able to forget their impacts for a long time. To end, here’s a speech from one of Subahibi’s characters, Minakami Yuki, that occurs around 3/4 of the way through the VN. Enjoy & live happily.