My Infinite Summer

Or How I Learned to Hunker Down In The Space Between Each Heartbeat and Make Each Heartbeat A Wall and Live In There

Attempting to write anything approaching a totalising ‘review’ of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest is sort of a joke. The book itself, a whopping 1079-page behemoth and the subject of notoriety amongst 4chan /lit/ bros and (strangely) much academic dismissal amongst hardcore literary critics, Infinite Jest was what I settled on as my yearly ‘book of the summer’; I’ve kept up this ritual of immersing myself in a giant novel during my midsummer months for three years now.1

Yet, despite the foreboding reputation of this tome, as well as its both lexical and physical weight2, Infinite Jest is much more of a silly and fun read than the awestruck aforementioned lit bros made it out to be. For instance, nowhere within the online discussions of this book I mentally abosrbed via internet-osmosis was this book framed as a crazy sci-fi alt-history worldbuilding extravaganza; no way could I have predicted the magnetic campus-novel feel of its tennis academy scenes, nor its brutally realistic depictions of emotional abuse, domestic family drama and depression-induced pure & utter anhedonia.

Never before have I ever been so simultaneously baffled by and enamoured by a piece of literature. Perhaps its a side-effect of the book’s mammoth length or its too-close-to-home evocations of trauma and mental illness or its entirely batshit yet somehow bizarrely believable political landscape, but even though I officially put the book down a few hours ago, I have a feel I will be staying at Enfield Tennis Academy for a while, despite having already lived and breathed amongst its tennis courts and halls for the past month of my psychic life.

I’m not the best review-writer, generally; as I struggle with even recounting the plots of trite anime episodes to my mother, I doubt I will be able to outline the intricacies of DFW’s opus in anything resembling a coherent fashion - I cower from even attempting to describe the book’s setting, from trying to explain to the potential reader of this newsletter what the ‘Year of the Adult Depend Undergarment’ means or what ‘Eschaton’ is.

Instead, the rest of this newsletter shall be a vague attempt to cohere Infinite Jest’s themes, alongside its infuriatingly unresolvable ending, together in my own head - mostly as sort of souvenir for me to remember this wild literary experience and to give the book’s conclusion, and DFW’s memory, the honour it deserves in my psyche.

On the ending of his novel DFW said:

“There is an ending as far as I’m concerned. Certain kind of parallel lines are supposed to start converging in such a way that an “end” can be projected by the reader somewhere beyond the right frame. If no such convergence or projection occurred to you, then the book’s failed for you.”

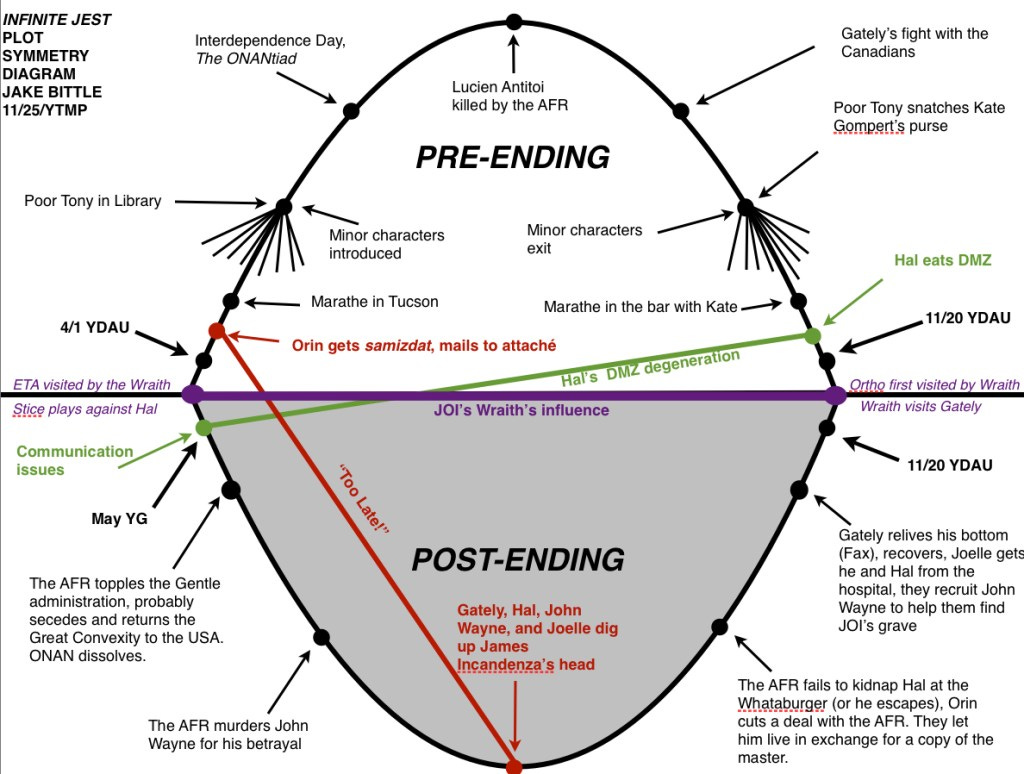

Despite the good intentions I’m assuming lay behind these words, the unfortunate consequence of them has been a hyper-obsessive and strange attempt on the part of many online fans of Infinite Jest to track, chart and theorise about the parabolic plot of this novel with the same directionless lunacy of Qanon conspiracy theorists and true-crime-solving-obsessed Redditors.

Me, I dislike this treating of the text like a bug under a microscope, like a corpse to be poked at, prodded at and dissected in fruitless attempts at drawing a straight narrative line. To me, the plot of the book is less about sussing out all its medical/political/mathematical/lexical complexities, and more about feeling it. I thus prefer this DFW quote much more that the previous one:

"Well, umm, I guess i would just come back to what kind of feels real in our tummy. Your classic sort of commercial art of which the easiest example would be the detective genre the whole thing is about establishing a puzzle and then resolving it somehow. It's not hard to make the argument that lot of mainstream realist fiction works the same way. But, I don't think irresolvability is really what feels real to me because once you've determined that something is in fact irresolvable, and it sounds like i'm just playing with words, but you've really resolved it. You know - unsolvable. I don't know about you but, it seems to me in all kinds of situations, some of which are very important, most of the energy goes into trying to decide whether it's worth spending energy trying to resolve it or not."

As mentioned above, Hal, one of the novel’s main characters, is maybe one of my favourite characters in a piece of fiction, ever. The opening of the book, starting as it does in the plot’s future with a scene of Hal having lost the ability to verbally communicate, has and continues to be a focal point around which much of the IJ-online-community’s theorising centres around - I have seen theories that Hal’s loss of speech was the cause of ingesting a piece of mould when he was a child (yes, really), that Hal lost his speech by being drugged with Madame Pyshosis3 by his best-friend Michael Pemulis4, that Hal lost his speech after being drugged by the wraith-ghost of his death father with same drug, amongst other more increasingly bizarre theories and ideas.

I mean, to each their own, death-of-the-author and stuff, but personally, I interpret Hal’s silence as the inevitable consequence of his depression and unresolved-trauma induced solipsism that only heightens and worsens as the book continues and Hal gets more and more abstracted from reality. As a narrative foil to the novel’s other sort-of-main-character Don Gately, who recovers from his abusive childhood and subsequent narcotic addiction by branching out and connecting with the community and culture of the novel’s enamouringly-depicted drug rehab Ennett House, Hal lets his trauma sit and rot within him silently; he continues playing tennis, interacting half-heartedly with those around him and feigning and human normalcy despite the everlasting havoc his trauma and sadness are internally wreaking on his emotional ability to feel and his human abilities to function and communicate. It is arguably during Hal’s forced drug withdrawal that occurs 3/4ths of the way through the book, during which he tries but fails to ask for help, that all his horrible and sick and inhuman feelings coming rushing to the surface, corrupting him for life and robbing him of the simplest of human attributes - to speak, to blend in.

The traumatic impacts of domestic abuse are further suggested in regards to the the titular Infinite Jest - the Master Tape of Hal’s movie-director dad’s lost movie, a film purportedly made by the father to communicate with his increasingly self-isolating son and where most of the novels parallel and refracted narratives seem to somewhat converge. The film itself, a shakily-filmed video of semi-main-character Joelle Van Dyne aka Madame Psychosis revealing to the viewer that one’s mother is the person who killed them in their previous life, all as an injunction to accept the inevitability of death, is also where the novels themes really coalesce. Specifically, the movie evokes for both its fictional viewers and its meta-fictional readers the intertwined nature of childhood trauma and the urge to self destruct, with the double entendre of Madame Psychosis’ name (both the name of the infamous DMZ drug and of semi-main-character prettiest-girl-of-all-time Joelle Van Dyne) presenting two options to the viewer-reader-made-child in the wake of trauma - either losing oneself to the alienation of addiction to the mould and rot of substance abuse and stasis, or reaching beyond this solipism to the novel’s opposing humanistic themes and accepting one’s trauma. The book itself arguably exists in-between two spectrums of drug-medical-trauma jargon and character realism and true emotion - it is up to readers which interpretation they choose to fall into, though by the novel’s end Hal is tragically forced into the former.

To quote reddit user LEWDWARD, in a post from 4 years ago:

“One of my favorite things about Jest (is that)wWe can provide our own explanations for Hal’s degeneration (DMZ, Mold, Addiction, The Entertainment, Intervention of Wraiths) but what we cannot deny is the sensation of degeneration. We are met at the books inception with a internally composed but outwardly dysfunctional Hal, the opposite is true of the Hal we get to know in his time on the hill.

What remains compelling to me when trying on new interpretations of the literal events of IJ is the emotional force of each scene. A mold may be a fungus, a parent-child relationship, international relations, or a concavity/convexity. There are myriad knots and beauty in the thread that ties.”

So what about the hypothetical post-ending grave-digging scene, or what happens to the Master Tape of Hal’s movie-director dad’s lost movie, the titular Infinite Jest; what about Orin, and the wheelchair assassins and the incestuous undertones suggested again and again in regards to Hal’s mother Avril Incandenza? Are these just untoward red herrings?

God forbid me from pretending to be an expert on this 1049 page giant of a novel! All the above theorising is probably very puerile and ironically solipsistic - all very much from my own perspective and in regards to how and where the novel lodged itself into my psyche and heart. My opinions of the novel are nowhere near objective and come from the sort of lens Joelle Van Dyne describes as used during the filming of the notorious Infinite Jest cartridge:

“Well I've never been around them. But I know there's something wobbled and weird about their vision, supposedly. I think the newer-born they are, the more the wobble. Plus I think a milky blur. Neonatal nystagmus. I don't know where I heard that term. I don't remember. It could have been Jim. It could have been the son. What I know about infants personally you couJd — it may have been an astigmatic lens. I don't think there's much doubt the lens was supposed to reproduce an infantile visual field. That's what you could feel was driving the scene. My face wasn't important. You never got the sense it was meant to be captured realistically by this lens.”

To end, I love this book endlessly; despite its objective difficulty and unresolveability, I feel like its undeniable emotional core struck me deeply and will stay with me for a while. Finally, here is my favourite quote from the tome, from the perspective of one Don Gately on how to Abide5 one’s pain and suffering:

“He could do the dextral pain the same way: Abiding. No one single instant of it was unendurable. Here was a second right here: he endured it. What was undealable-with was the thought of all the instants all lined up and stretching ahead, glittering. (…) It's too much to think about. To Abide there. But none of it's as of now real. What's real is the tube and Noxzema and pain. And this could be done just like the Old Cold Bird. He could just hunker down in the space between each heartbeat and make each heartbeat a wall and live in there.”6

This selection was made before I found out about ‘Infinite Summer’ - a 2009, internet-hosted reading group that tackled the novel in the summer after DFW’s death in a gesture meant to be appreciative that feels, to me, a bit odd, timing-wise.

A nightmare to carry around on trains/buses etc.

Street argot for the incredibly potent DMZ (hallucinogenic?)

Who he is so very homo-erotically in love with by the way. Subtextually.

AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) terminology

Also, of course this review is footnoted - I couldn’t resist I simply couldn’t resist it. RIP David Foster Wallace. 10/08/2025.